What is Zen Art? 20 Japanese Masterpieces You Should See

by Jes Kalled & Lucy Dayman | ART

Old Plum, Kano Sansetsu, 1646, Met Museum

A practice in appreciating simplicity, Zen art grew up around the philosophy of Zen Buddhism. Despite its religious underpinnings, the impact and evolution of the form traverse both spirituality and everyday culture.

In Japan, where Zen has long been entwined in the cultural DNA of the nation, painting and calligraphy became two important vehicles for spreading the message of Zen masters to their students. An amalgamation of spirituality, education, culture, and creativity, Zen art is at times difficult to articulately classify, but is infinitely fascinating. From the history, key artists, essential locations and its modern rebirth, here’s a crash course in everything Zen art.

What is Zen Buddhism?

The evolution of Zen Buddhism in Japan is a topic about which numerous books have been written. Given the profound and far-reaching influence of Buddhism in Japanese life, there’s no way to do it justice in one article. However, some context is essential for those interested in Zen art.

Tsuba Sword Guard with Figure of Daruma, 18th Century, Met Museum

Zen is just one of many sects of Buddhism. The sect known as Chan was the creation of Buddhist monk Bodhidharma, who came from India and later settled in China. It’s thought that around the 7th century Chinese Buddhist missionaries introduced Chan to Japan, where it became known as Zen. Meditation, also known as zazen is at the core of all Zen Buddhist philosophies. Followers believe meditation leads to self-discovery and enlightenment. Essentially, without meditation, there would be no Zen.

Wood and Lacquer Statue of a Rakan or Englightened Person, 17th Century, Met Museum

Zen Buddhist philosophy strongly follows the idea that that self-centric thinking or ego is detrimental to enlightenment, keeping one entrapped in the human world. To free oneself from this world, Zen practictioners meditate, clearing their minds of superfluous thoughts and freeing themselves from human shackles.

What is Zen Art?

Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi River on a Reed, Kano Soshu, 16th Century, Met Museum

The barriers between human existence and reaching enlightenment are the primary catalyst for so many works of Zen painting. This is epitomised in the historic piece Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi River on a Reed, by artist Kano Soshu (1551–1601). An elegantly simple ink illustration of Buddhist monk Bodhidharma (known in Japanese as Daruma), the image carries with it the mentality that you don’t need extravagance to have a meaningful existence. Less is more!

Old Plum, Kano Sansetsu, 1646, Met Museum

Although Zen prizes simplicity, the art of Zen isn’t always minimalistic in style. Iconic artist Kano Sansetsu’s visual outputs were incredibly bold. His four sliding-door panel painting Old Plum (1646) was once part of Myoshinji temple’s sub-temple Tenshoin in Kyoto. Featuring the thick, black, twisting trunk of a plum tree, this work would have once been the backdrop to a Shoin Room, a room used for study in a Zen monastery.

Old Plum, Kano Sansetsu, 1646, Met Museum

At first Zen art typically represented religious figures, but as the time passed, more secular imagery was explored, and bamboo, flowering plums, orchids were some of the regularly featured motifs.

If you want to know more about how Japanese art came to be how it is today, check out: All You Need to Know About Japanese Art! But for now we take a look at examples of Japanese zen art, and where you can see it!

1. Portrait of Daruma

Orchids and Rocks by Gyokuen Bonpo, 14th-15th Century, Met Museum

Perhaps one of the most prevalent subjects of Zen art is that of the Daruma. Interestingly, Daruma is a Japanese language abbreviation of the Sanskrit Bodhidharma, or rather, the founder of Zen Buddhism. Daruma was born in the 6th century in India, and is thought to have taken his teachings to China thereafter. Notably this portrait bears no added background, just a stark bareness; representative of the ‘nothingness’ of Zen philosophy. The artist responsible for this profile was Unkoku Togan. He took Buddhist vows while living in a temple building in Yamaguchi called “Hermitage in the Valley of the Clouds,” thus most of his paintings were immersed in his own Zen learnings. To find out more about the modern incarnation of daruma, check out What are Daruma? 6 Things to Know about Daruma Dolls.

2. Daruma in a Boat

Daruma in a Boat with an Attendant, Suzuki Harunobu, 1767, Met Museum

Ukiyo-e, Japanese woodblock prints, is one of Japan’s most famous art forms and one we’ve covered extensively in previous articles (such as Hokusai’s Iconic Images of Mount Fuji). Given its ubiquity on the art landscape, it’s a not a surprise that many impressive works of Zen Buddhism exist in this form. One highlight of this art form is Daruma in a Boat with an Attendant by Suzuki Harunobu (1767).

What makes this piece worth mentioning is its visual message. Quite unlike what we’d expect from Daruma, the founder of Zen Buddhism, to be like, this image sees him plucking hairs from his chin in a display of complete vanity. Ukiyo-e artists have long had a reputation for producing works with that throw a critical eye on cultural norms and expectations, and the hypocrisy of society. Daruma during the Edo-Period became a slang term for a courtesan, while the word darumaya meant a brothel; this image is a play on those concepts.

3. Buffalo and Herdsman

Buffalo and Herdsman, Kawanabe Kyosai, 1887, Met Museum

A century after Daruma in a Boat with an Attendant, Kawanabe Kyosai created Buffalo and Herdsman, a stunning interpretation of the Buddhist parable Ten Scenes with an Ox. In this story, an ox is found by a boy (who is meant to represent religious training), who ropes the beast and leads it on the right path home (or to ‘enlightenment’ for those reading between the lines).

4. Gibbons Reaching for the Moon

Gibbons Reaching for the Moon, Ito Jakuchu, 1770, Kimbell Art Museum

One other reason why Zen Buddhist art is so popular and admired is that these ideas of Zen Buddhist philosophy are often best described through imagery as opposed to written form. Take Two Gibbons Reaching for the Moon (1770) by Ito Jakuchu as an example. The image is an analogy for the bad human habit of trying to attain the unreal (the unreal here being the reflection of the moon in the water), when what we should be after is spiritual sustenance.

5. Enso Hanging Scroll

Enso by Bankei Yotaku, 17th Century, Johnson Museum of Art

Enso, is a circle that is usually made in one simple brush stroke. It’s something that is thought to be made when the mind is liberated from constraint, and free to create what it wants to. It symbolizes mu, which means the void, or nothingness, and represents the aesthetics of Zen and minimalism we still recognize today. The enso is also thought to help with meditation practice. The circle is a representation of the mind reaching a state of fullness and emptiness. This particular ink hanging scroll of ink on paper was made by artist Bakei Yotaku (1622 - 1693). Rather uniquely, Yotaku uses two brush strokes to create this enso.

6. Zen and Ink Painting

Patriarchs of Zen Buddhism by Kano Motonobu, 16th Century, Tokyo National Museum

Kano Motonobu, son of the famous Kano Masanobu (founder of Chinese-style painting school), used Chinese ink landscaping techniques when painting. Here in this ink painting, the practice and spirituality of Zen can be felt in the characterization of its patriarchal masters. Within the construction of Motonobu’s work, his use of color is distinctive, and helped to convey the Zen narrative of “awakening” that occurs within its subjects. Throughout this era, ink painting was used to express the delicate aesthetics of nature and people. A painting that tells a story.

7. Dragon and Tiger

Dragons and Tigers by Kano Sanraku, 17th Century

On the other end of the Zen spectrum of art, are the pieces that seem alive, thriving, and ready to bite you. Among these is Dragon and Tiger (17th century) by Kano Sanraku. These creatures were thought to be the protectors. The tiger specifically represents the soil and earth, grounded beings who might not be seen in everyday life but can be found in this world and are very real. Many paintings of both dragons and tigers can be found in Japanese Buddhist temples.

8. Tofukuji Zen garden

© Interaction Green, Tofukuji Garden

Tofukuji Zen garden was designed by Mirei Shigemori in 1938. The Tofukuji temple was founded hundreds of years prior in the 13th century. Much research was conducted by Shigemori before implementing the zen garden that can still now be seen at the Kyoto temple. In the East Garden, one can find the big dipper as expressed by re-used pillars in the ground. The South Garden is made up of dark rocks, an element Shigemori often used, and green mounds of grass that represent the five prominent Zen temples in Kyoto. In each space, one can feel the characteristics of traditional Zen architecture—the absence of human interference, and yet here there is somewhat of a blend and balance of such. Perhaps most notable is the silence at Tofukuji, an absence of sound and interruption.

9. Orchids and Rock

Orchids and Rocks by Gyokuen Bonpo, 14th-15th Century, Met Museum

Orchids and Rock by artist Gyokuen Bonpo is a hanging scroll; ink on paper that dates back to the late 14th and early 15th century. The artist was an esteemed Zen monk, poet and calligrapher who painted as a pastime and was largely influenced by literati: scholar-officials in Chinese society. Bonpo often chose orchids and rocks to be the subject of his calligraphy, likely due to the fact that orchids were known for their resilience to grow in low-quality soil. In literati lore, orchids were symbols of purity and loyalty.

10. Rahula from a Set of the Seated Eighteen Arhats

Rahula by Fan Daosheng, 1664

Inside the Obaku-san Manpuku-ji temple in Kyoto sits a statue by the name of Rahula. The sculpture depicts the son and disciple of Buddha (Siddartha Guatama). Here he is depicted opening his chest to reveal the face of Buddha, suggesting we all have Buddha inside of us, and thus all have the potential to reach enlightenment. The temple was founded in 1661 as an homage to the Wanfu Temple, located in the mountains in Fuzhou, China. The founder, Ingen Zenji, brought many Zen-Buddhist teachings from China to Japan throughout his many visits and eventually his move to Japan. Ingen Zenji invited Fan Daosheng to the temple to sculpt Rahula, the buddhist statue.

11. Kintsugi

© Zen, Kintsugi

Kin in Japanese means gold, tsugi in Japanese means joining together. The artistic practice of kintsugi is the joining of once broken ceramics with gold lacquer in order to create a repaired piece. The restoration process embodies the acceptance aspect of Zen, where we are not meant to look away from mistakes or fractures in life, but rather accept their existence as a part of life. By acknowledging one’s history and celebrating imperfection, both we, and the ceramics made in kintsugi can live a more peaceful, and balanced life.

12. River Landscape

River Landscape by Unkoku Tohan, 17th-18th Century

Made by Unkoku Tohan (1635-1724), River Landscape, is yet another great example of visual representation in Zen art in the Edo period. Tohan was self-proclaimed 6th generation Sesshu, after Toyo Sesshu, a distinguished Zen-Buddhist painter of ink paintings, or sumi-e. This traditional style of painting, though adapted from a Chinese origin, became distinctively Japanese by his hand. The Unkoku school of art would later continue the Sesshu style and legacy.

13. Black Raku Tea Bowl

Black Raku Bowl, 1800, Denver Art Museum

Wabi: a taste for the simple and quiet. Sabi: the rust of age. Together, wabi sabi is the feeling that encourages the acceptance of impermanence. More specifically, the feeling of wabi sabi gives us information that everything is always changing, and that nothing is ever complete nor perfect. To suggest that something should be complete or perfect would not be true. The Black Raku tea bowl represents something that is simple, austere, and imperfect, thus making it true. This type of tea bowl was used for Japanese tea ceremonies.

14. Modern Zen Design House

© RCK Design, Modern Zen House

Architect, Ryushi Kojima, designed Modern Zen Design House in 2012 in Tokyo. Kojima said, “ [It’s] not about living in empty rooms or areas, but about creating true well-being for body and soul.” The two-story house creates space where there is little. Tokyo, a crowded compact metropolis, is quite the Zen challenger. Modern Design House I is an example of how to find that peaceful space within a space that wouldn’t normally allow for it. Such is the way of Zen, and such is the way of how Zen has found its way into design.

15. Haiku Poems

Dewdrop, let me cleanse

in your brief

sweet waters...

These dark hands of life

Haiku are poems that must be 5, 7, 5 in syllables. But this is more of an English form. The original Japanese form takes sounds and breath into account, and are typically shorter than the English counterparts that followed in later years. Matsuo Basho described haiku as “Simply what is happening in this place at this moment.” What is human, what is nature, what is happening is reflected in these short, three-lined poems. In Matsuo Basho’s poem Dewdrop, let me cleanse, the reader can experience his connection to nature, his seeking relief from pain, his surrender to the imperfection of life. It feels no surprise that the haiku was created by Zen monks.

16. Shinshoji Zen Museum and Gardens

The Shinshoji Zen Museum and Gardens is designed for the modern person to experience the ways of Zen. Practices such as tea ceremony, mediation, walks through Zen gardens, and taking a bath are at a person’s disposal. The complex itself is located in Hiroshima prefecture. And the concept is to embody and explore Zen at one’s own pace. The campus consists of museums and art installations. KOHTEI, an art pavilion shaped like a giant ship, can also be found at the Shinshoji temple. All in all, this location is a place where one can immerse oneself in the attributes of Zen, both traditional and modern though the interpretations may be. Take a look at Japanese Tea Houses: All You Need to Know About Chashitsu to find out more.

17. Hotei in the Guise of a Street Performer

Hotei in the Guise of a Street Performer by Hakuin Ekaku, 18th Century, NOMA

One of the most influential Zen masters was Hakuin Ekaku (1686 - 1769). During the time of Ekaku, Japan was under the Tokugawa shogunate rule. Government sponsorship of Zen institutions dwindled to an end, however, Zen art found a new way to thrive. This in part can be seen in the examples done by Ekaku, who found new and different ways to express Zen through inviting other aspects of life into the work such as: folklore, Shinto gods, and daily life scenes.

18. Zen and the Art of the Tea Ceremony

© Mizuno Toshikata, The Tea Ceremony, 1900s

Zen isn’t all just about meditating and studying though, the tea ceremony is another manifestation of traditional Zen culture and art. Before it became popular in Japan, many Chinese Chan monks would drink tea to stay awake during long sessions of meditation. When in the 9th century Buddhist monks travelled to China to study, they brought back with them tea leaves and a fresh way to brew it; mixing hot water and ground up leaves with a whisk. This was the beginning of the Japanese tea ceremony.

19. Tea Utensils

Ceramic Teawear, Musée des Beaux Arts de Lyon

The version of the traditional Japanese tea ceremony we see today was created by a former Zen monk, Murata Shuko, who called the practice wabi-cha (wabi in Japanese is an appreciation of both simplicity and the transience of everything). This practice is immortalised in the creation of tea ceremony ceramics. Typically utilising elegantly simple earthenware cups, vases and bowls; the tools used for the service are a practical, physical embodiment of the Zen philosophy.

Click here to found out more about the 19 Essential Japanese Tea Ceremony Utensils!

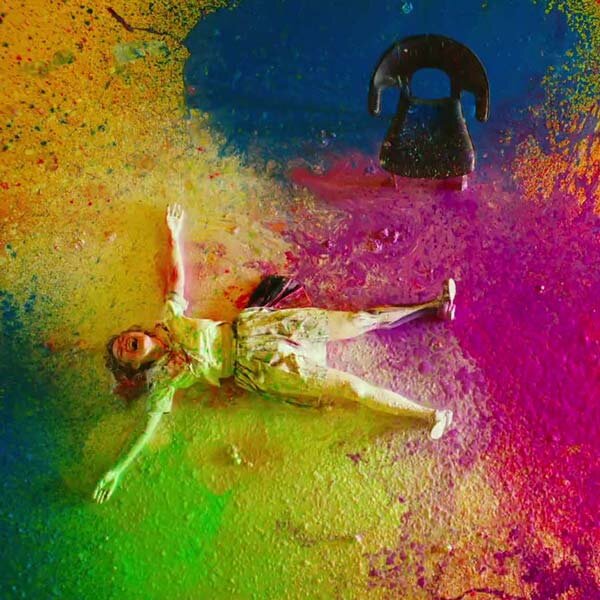

20. Ten Great Disciples of Buddha

© Shiko Munaka, Samantabhadra, National Gallery of Victoria

Although its history goes deep, Zen art and design isn’t suspended in time. Even if its philosophies are about reaching beyond the human physical realm, the artists that created the work are still influenced by the very human field of modern art.

One of the best examples of the form’s transformation is Shiko Munakata's woodblock prints. Munakata was generally regarded as the greatest woodblock printer of the twentieth century. His Ten Great Disciples of Buddha (1939/1948) series saw traditional spiritual themes reimagined in a folk art form with an almost Picasso-esque, modern, cubist perspective.

Where to See Zen Buddhist Art?

1. Gohyaku Rakanji, Tokyo

One of the most incredible Zen experiences you can have in Japan is paying a visit to Gohyaku Rakanji in Meguro. Here you’ll meet hundreds up hundreds of Rakan ascetic beings who take care of the rules of Buddhist law here on earth. Crafted over a decade, monk and sculptor Shoun Genkei created 500 of these figures, many of which you can still admire today.

Address: 3-20-11 Shimomeguro, Meguro, Tokyo (see map)

2. The Museum of Zen Culture and History, Tokyo

© The Museum of Zen Culture and History

If you’re in Tokyo and want to learn more about the evolution of the art, be sure to pay a visit to The Museum of Zen Culture and History. Part of Komazawa University, the museum is open to the public and houses both temporary and permanent exhibits covering all facets of Buddhism, including of course Zen art.

Address: 1-23-1 Komazawa, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo (see map)

3. Nanzen-ji, Kyoto

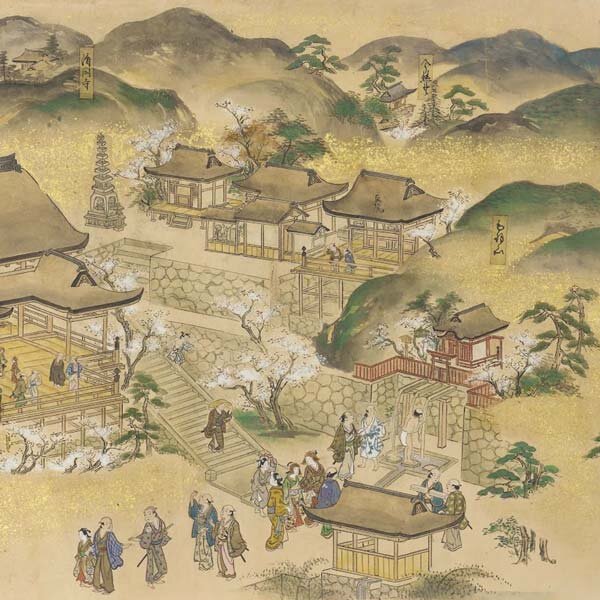

Scenes in and around the Capital, 17th Century, Met Museum

In Japan’s most famous historical city, Kyoto is where you’ll find Nanzen-ji. Founded during the 13th century, it was an influential icon of the popularization of Zen Buddhism across Japan. Known as one of the most stunning temples in the city, its intricate design, and rock garden, has made it a must-visit destination for those exploring Kyoto’s connection to Zen, which is perfectly captured in the six-panel 17th century image Scenes in and around the Capital.

Address: Nanzenji Fujuchicho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto (see map)

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki, Available at Amazon

Shunryu Suzuki offers an introduction to the way of Zen. Zen as lifestyle, as philosophy, as practice, and way. The author popularized Zen in the United States, having founded a Zen Buddhist monastery in San Francisco, California, the first one outside of Asia. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind opens with the question What am I? And expands upon the principles of zen from the physical sitting practice of zazen to understanding one’s true nature; the acceptance and non judgment of the mind.

JO SELECTS offers helpful suggestions, and genuine recommendations for high-quality, authentic Japanese art & design. We know how difficult it is to search for Japanese artists, artisans and designers on the vast internet, so we came up with this lifestyle guide to highlight the most inspiring Japanese artworks, designs and products for your everyday needs.

All product suggestions are independently selected and individually reviewed. We try our best to update information, but all prices and availability are subject to change. As an Amazon Associate, Japan Objects earns from qualifying purchases.

ART | October 6, 2023