What is a Yokai? 15 Mysterious Japanese Demons

by Teni Wada & Ahmed Juhany | ART

Gong Held by Oni in Wood an Lacquer, 19th Century, the Met Museum

Interest in Japanese yokai culture has exploded in recent years. Painting and prints of shape-shifting animals, water-spirits and city ghouls are emerging at exhibitions all around Japan, and across the world.

The eerie and strange has long influenced Japanese art. It’s a fascination that’s been enjoyed and nurtured over many centuries, and today these Japanese mythical creatures can be appreciated everywhere, from museum halls to renowned Ghibli films, like My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away.

But what is a yokai, where are they from, and what do they do? Read on to discover more about the haunting realm of yokai.

What Does Yokai Mean?

Hyakki Yako by Kawanabe Kyosai, 19th Century

Yokai is not simply the Japanese word for demon, as is sometimes believed. They are the embodiment of a moment: a feeling of dread and bewilderment, or awe and wonder over an extraordinary event; or a strange sound or peculiar scent that demands an explanation; an ineffable phenomenon explained only by a supernatural entity. Little wonder then that the Japanese characters for Yokai are 妖怪, which taken individually could mean strange or alluring mystery!

Where Do Yokai Come From?

One Hundred Monsters by Toriyama Sekien, the Met Museum

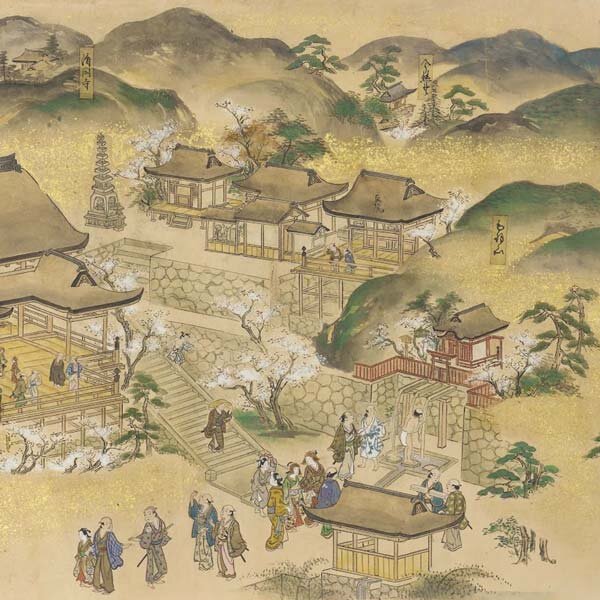

Yokai had existed in Japanese folklore for centuries, but was during the Edo period (17th-19th centuries) that they began to be widely seen in art. It is no coincidence that their rise to the forefront of artistic culture began at a time when the printing press and publishing technology became widespread.

One of the oldest examples of yokai art was the Hyakki Yagyo Zu, a 16th century scroll that portrayed a pandemonium of Japanese monsters. This formed the basis for Japan’s first definitive encyclopedia of yokai characters through the work of 18th century printmaker Toriyama Sekien. Using the newly developed technologies of woodblock printing, Sekien was able to mass-produce yokai illustrations in his own catalogs of the monster parade. How many yokai are there? The series was known as Gazu Hyakki Yagyo series, meaning Illustrated Night Parade of a Hundred Spirits, although in this context, one hundred just means many! These three texts illustrate more than two hundred of these Japanese demons, each with its own brief description and commentary.

Shokuin from One Hundred Monsters by Toriyama Sekien, the Met Museum

Here, in his third book, Konjaku Hyakki Shui (Supplement to The Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past), Sekien finds inspiration in Chinese mythology. He details a spirit named Shokuin that haunts Nanjing’s Purple Mountain. It appears as a red, man-faced dragon, which looms over the mountain a thousand meters tall.

Kiyohime from One Hundred Monsters by Toriyama Sekien, the Met Museum

Much of Sekien’s work may seem familiar to fans of modern Japanese horror films. His illustration of the Kiyohime - a woman that fell in love with a priest and was transformed into a terrifying serpent demon through the rage of unrequited love - is a prime example of a style that would go on to inspire many artists in the horror genre.

This is not just another rendition of the old, dried-up vengeful ghost tale that we are used to seeing. It is a twisting and morphing of something once familiar to the reader, until it no longer was. By merging the natural with the unnatural, a woman and a serpent, Sekien strips away the reader’s sense of security by infecting what was previously normal.

What Are Some Famous Yokai?

1. Amabie

Amabie, 2003, Kyoto University

This three-legged aquatic creature might be an unlikely contender in the global fight against COVID-19. The first and only recording sighting of an amabie was documented by a government official in the mid-19th century. According to his report, he ventured off to sea to investigate the source of a strange light. When he approached the light, an Amabie emerged to inform him of a bountiful harvest that would last for 6 years.

However, should disease occur, one can keep disease and calamity at bay by simply sharing an image of its likeness with others, which prompted Twitter users in Japan to share images of an Amabie with the hashtag #amabiechallenge. In fact, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has even used images of amabie in its initial campaign in the fight against the coronavirus!

2. Tatsu

Tatsu (Dragon) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 19th Century, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Tatsu, or Japanese dragons, are water-dwelling yokai similar in appearance to dragons of Western medieval lore. While many are benevolent creatures who respond to the prayers of humans, others are terrifying beings inflicting terror upon humans.

The Tatsu has male qualities and is often paired with the feminine, phoenix-like houou to symbolize yin and yang. In some forms it is also capable of shape-shifting, such as the sea god Ryujin. According to legend, the Japanese imperial family is descended from dragons, specifically the daughter of Ryujin, who bore a son that later became the father of Japan's first emperor.

In modern day Japan, the Tatsu continues to be a revered yokai; they can be found on the grounds of temples and shrines. Many festivals are held in celebration of these powerful beings, such as the Kiyomizu Temple Seiryu-e Dragon Festival honoring the dragon that drinks the water underneath the main hall of the Kyoto temple.

3. Kirin

Kirin by Kikuoka Mitsuyuki, 18th Century, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Kirin is a serene and majestic fire-breathing, horned creature symbolizing purity, justice, and wisdom. It is about the size of an adult deer, with dragon-like scales all over its flaming body. Its origins stem from Chinese mythology and its powers surpass those of the phoenix-like houou and tatsu dragon.

Interestingly enough, the Japanese word for giraffe is also kirin, perhaps because the African animal shares similarities with the Kirin: horns, scale-like patterned skin, and long legs. The Kirin is also the mascot for the Japanese beverage company, Kirin. In fact, if you look closely at the image on any Kirin Product, you’ll find the Japanese symbols for Kirin embedded within its flowing mane.

4. Ningyo

Ningyo (Mermaid) by Tadayoshi, 19th Century, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Forget whatever children’s animated stories taught you about mermaids, because the Japanese Ningyo is no enchanting songstress. Rather, Ningyo are more fish-like than human in appearance with golden scales, long fingers, and sharp talons.

If one were able to successfully capture a Ningyo and feast on its flesh, they would be granted eternal life, prompting many fool-hardly fishermen to attempt to capture one. However, if one is not successful in capturing a Ningyo, they may be cursed or their entire village may be wiped away by a large wave. Likewise, to accidentally catch a Ningyo in one’s net is also a harbinger of misfortune, so one must return any captured Ningyo to the sea immediately.

5. Zashiki Warashi

Zashiki Warashi

Ever feel like you’re always misplacing your phone, glasses, or keys? You’re not going crazy, it might all just be the work of a very cheeky Zashiki Warashi! These yokai are mischievous pranksters that resemble human children, though they are only visible to residents of a home.

Unlike ghosts and other spiritual beings, to have Zashiki Warashi in one’s home is a blessing as they invite fortune and good luck. Once the presence of Zashiki Warashi has been confirmed in one’s home, great care should be taken in order to them there by leaving out candies or food for them at night. Should a Zashiki Warashi disappear from a residence for any reason, misfortune may befall the home and its residents.

6. Tanuki

Tanuki by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1843, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Japanese racoon dogs, or Tanuki, are mischievous tricksters often depicted with a bottle of sake, rather comically large testicles and wearing a straw hat. Statues of these magical, shapeshifting creatures are typically found outside restaurants and bars coyly inviting diners to drink, dine, and spend money.

The Tanuki is rivalved only by the Kitsune in terms of popularity and magical ability in modern Japanese folklore. It is said that Chingodo Shrine in Tokyo’s historical Asakusa district is dedicated to Tanuki as the presence of tanuki residing on its grounds allowed it to survive the air raids of World War II. Today, the shrine is an important place for people to pray for protection from fire and theft. Rakugo storytellers, kabuki actors, and other entertainers also pray at Chingodo Shrine for success in the entertainment world.

7. Kitsune/Yako

Kyubi no Kitsune (Nine-Tailed Fox) by Ogata Gekko, 1893, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Cunning, intelligent, and mischievous, the Kitsune, or Japanese fox, are shape-shifting yokai similar in appearance to wild foxes. Kitsune fall into one of two groups: spiritual beings that act as messengers to the gods and wood-dwelling creatures that deceive or prank unsuspecting humans.

Messenger foxes are associated with Inari, the Shinto deity of rice rice cultivation who is also associated with prosperity. Inari shrines, such as the famous Fushimi Inari-Taisha of Kyoto, are easily recognizable by their vermilion torii gates and images of foxes. Wild Kitsune, on the other hand, enjoy tricking humans and are even known to possess humans as well.

8. Yamanba

Yamanba by Tsukioka Kogyo, 1924, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Nearly 70 percent of Japan’s total land area is mountainous, which means there’s a pretty good chance you could run into a Yamanba (mountain hag) during your next hike!

Yamanba, also known as Yamauba, reside in the mountains and forests of Japan as recluses. They disguise themselves as kind eldery ladies offering lodging and meals to lost or weary hikers before revealing their true identity as an evil witch once their unsuspecting victim is asleep.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the term “yamanba” was once used in a derogatory manner to describe extreme adherents of Shibuya gyaru fashion. However, these trendsetters proudly reclaimed the word as a means to celebrate their devotion to dark, tanned skin, bleached blonde locks, and frosted eyeshadow.

9. Yuki Onna

Yuki Onna (The Snow Woman) by Uemura Shoen, 1922, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Japanese Alps are home to some of the country’s most scenic winter towns, including the thatched-roof farmhouses in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, Shirakawa-go in Gifu Prefecture. However, take care when a heavy snowstorm approaches because it could mean that Yuki Onna is not too far away! These yokai are deadly beauties with long, black hair and skin as smooth and white as marble, killing their victims with an icy kiss of death.

Yuki Onna, however, are known to fall in love on occasion, though, in these accounts, the unsuspecting husband discovers his wife’s otherworldly roots after years of marriage to an “ageless” being. In other versions, Yuki Onna melts away after soaking in a hot bath at her husband’s insistence.

10. Tsuchigumo

Tsuchigumo by Adachi Ginko, 1885, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Tsuchigumo are enormous spiders that can grow to an incredible size, large enough to take on an entire army! In fact, the term tsuchigumo is used in historical documents composed during the warring states period to refer to rebel factions.

The Tsuchigumo as a yokai is also a formidable and deadly foe. The 14th century scroll, Tsuchigumo Soshi, is a riveting tale of the battle between Minamoto no Yorimitsu of the Fujiwara Clan and his epic battle with a Tsuchigumo. In some versions of the legend, Minamoto no Yorimitsu battles a shape-shifting woman who reveals herself to be a monstrous Tsuchigumo with a belly full of baby spiders ready for battle.

11. Tengu

Tengu Masks, 18th Century, the Met Museum

The tengu is one of the best-known types of Japanese yokai, often intertwined with stories of mountain spirits and forest dwellers. The tengu has a long history, appearing in multiple ancient texts and adopting various images and representations, until it’s basic form was settled in the medieval period.

The eighteenth century iron masks above displays the most recognizable and contemporary depiction of the Tengu on the left, beside the older, more traditional representation on the right. Contrary to its original portrayal, the new Tengu is unfeathered and unbeaked. It is no longer a monstrous bird but an almost anthropomorphic being.

Find out more in 10 Things You Didn’t Know About Traditional Japanese Masks.

12. Kappa

Kappa Netsuke, 18th Century, the Met Museum

The kappa is a green, turtle-like humanoid, with webbed hands and feet and a carapace on its back. Atop its head is a dish-like indentation filled with water, which the kappa balances carefully. It is weakened if the content of the dish is spilled.

The boundary between kappa ad other kinds of creatures is blurred. But as is the case with most Japanese yokai, its name is suggestive. Lying between the periphery of the known and unknown, a yokai is named after the impressions it leaves or after its reported characteristics. Since the kappa is child-sized and lingers around rivers, its name is a mere combination of the words child and river.

This 19th century netsuke carves out the fundamental features of the Kappa. Its scaled, short arms and its sharp long claws were once widely feared, but now, the aged kappa is viewed with a certain humor and mockery over its child-like physique.

13. Yurei

Yurei by Utagawa Toyokuni I, 1812, the Met Museum

If the realm of contemporary Japanese horror could be encapsulated by a single yokai, then that yokai would be the yurei (ghost). A yurei often resembles her former self, her living self, but in death is pale-skinned, arms dangling uselessly by her side.

A yurei is depicted in a white kimono, a burial gown used in Edo period funeral rituals. Her long, black hair is let down as tradition demands before a burial ceremony.

When renowned woodblock artist, Utagawa Toyokuni I, illustrated this picture in 1812 to accompany the Tale of Horror from the Yotsuya Station on the Tokaido Road, he masterfully provided us with what has become the definitive depiction of a yurei.

Toyokuni’s influence can also be felt through the works of his students. In particular, Utagawa Kuniyoshi shared his master’s fascination with Japanese monsters and demons. Find out Why Utagawa Kuniyoshi Was the Most Thrilling Woodblock Print Artist.

14. Oni

Oni, 19th Century, the Met Museum

The word oni has a long history. It first appeared in the ancient, 8th century texts, the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters) and Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan).

The descriptions of oni have changed dramatically over time, to the extent that scholars find it difficult to assess what constitutes as a typical depiction of the creature.

In this nineteenth century painting, the yokai is portrayed as a large, ogre-like beast with a frightening face.

Gong Held by Oni in Wood an Lacquer, 19th Century, the Met Museum

Yet here, in a sculpture from a slightly earlier time, we see a more intricate oni.

They retain their ogre-like features, and though they are pictured with horns and fangs, they have become far more anthropomorphic. Their facial expressions are no longer as brutish and they seem almost gimmicky with their over-pronounced noses and their bushy brows.

15. Ijin

Ijin are people from what is called Ikai, a world that is beyond our own. They are outsiders that have crossed the boundary that stands between two separate worlds, often to complete a task.

While there are many types of ijin, some pleasant and others malicious, most are said to be harmless. These types range from religious figures, to craftsmen, to beggars and pilgrims. The Daikokuten in this early, twentieth century painting, is an example of a benevolent ijin.

He is often described as the Japanese equivalent of the Hindu deity Mahakala, and as a god of wealth.

The painting above shows a typical expression of the Daikokuten, with his beaming smile and exaggerated, gigantic ears. He holds a golden mallet, which grants the child good fortune.

The yokai world is vast, and although it is becoming more popular than ever, it is easy to get lost in the repackaging of Japanese yokai culture to charm modern audiences. Today there is remarkable progress in the realm of yokai scholarship in Japan, so there has never been a better time to explore the history of the inexplicable and find out for yourself what really is a yokai!

ART | October 6, 2023