10 Things You Might Not Know About Traditional Japanese Masks

by Lucy Dayman | CRAFT

© Samurai Armor, 18th Century, the Met Museum

Japanese masks are an artform of unlimited variety. There are theater masks, tailored for each indivual character and mood; there are religious masks, the physical embodiment of spirits; and masks are also worn for festivals and celebrations, some peculiar to one small town, others in festivities across the country.

To understand the many types of Japanese masks a little better, we’ve put together a guide to some of Japan’s most famous, strange and fascinating masked characters.

1. Onnamen

© Onnamen Noh Mask, 18th Century, Fukuoka City Museum

Masks are an essential element of the centuries-old tradition of Noh theater, signifying to the audience many aspects of the wearer’s character. Whilst they obviously hide the actor’s expressions, they’re carefully carved to catch the stage light and change expression depending on the angle of the mask’s shadow.

Traditionally, women do not act in Noh, so their parts are played by men wearing onna-men, or women’s masks, which take on a variety of forms. Beautiful women are recerated in a number of forms including ko-omote, wakaonna, zo, and magojiro, while omiona are working-class women and fukai and shakumi masks represent older, middle age women. One mask worth looking out for it’s deigan, the woman so wise and worldly she has gold-rimmed eyes. In the image above, you can see an 18th century onnamen with a noticeable smile. This mask would be used to portray that the character was madly in love.

2. Hannya

Hannya Noh Mask, 18th Century, British Museum

Another major figure in Noh theatre is Hannya, a face so ingrained in Japanese culture it’s one you’ve probably seen before, and one that - somewhat strangely - is a popular tattoo motif. The fearsome Hannya is a jealous female demon. Like onnamen, Hannya masks display a complex number of emotional states depending on how the light catches the features of the mask. Like most Noh masks, this hannya was crafted from solid Japanese cedar.

When an actor wearing a Hannya mask looks directly at the audience they see an angry female face; however, if Hannya looks at the ground, the relected light creates the illusion almost as though she is crying.

The different colors of a Hannya mask represent the different standings of the character: a white mask means a woman of refined character, red is for those who are a little less refined, while the darkest of reds is reserved for the evilest of all the demons - a woman who has lost complete control of her jealousy.

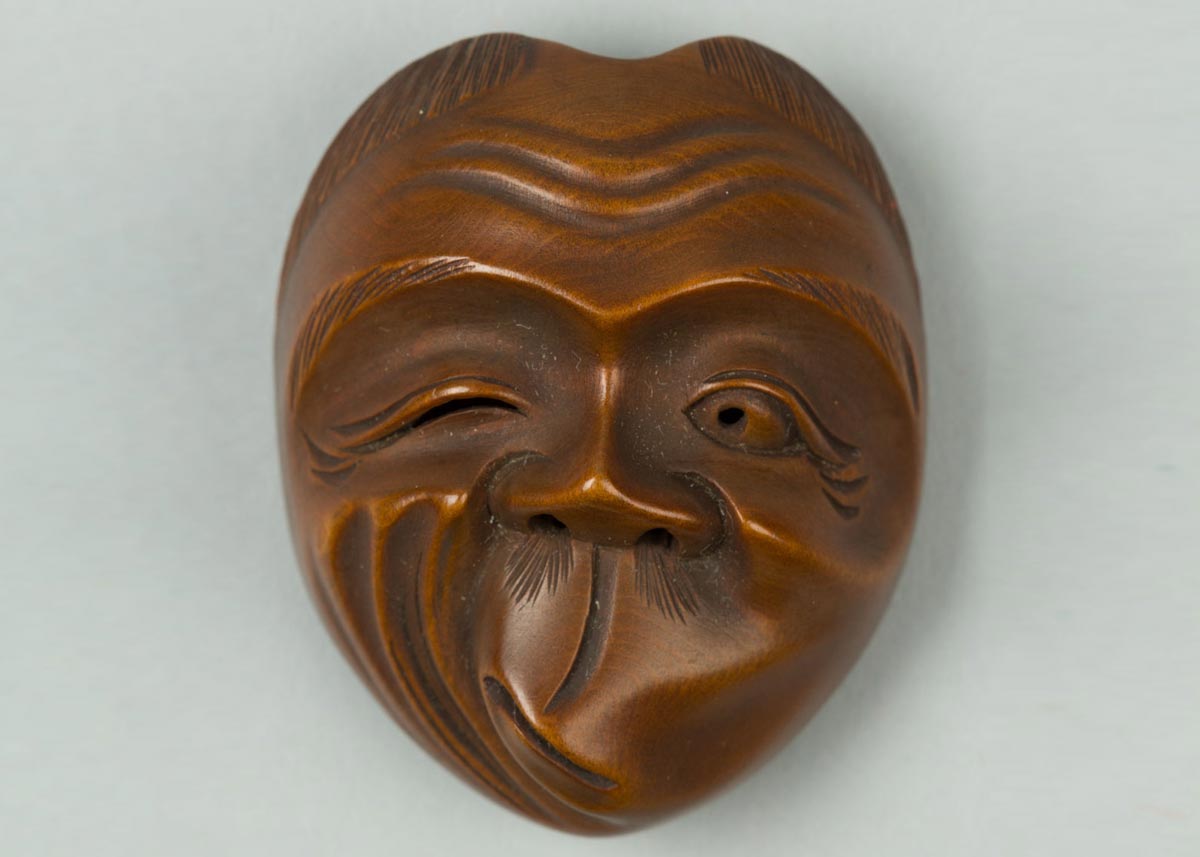

3. Hyottoko

Wooden Hyottoko Mask, 19th Century, the Met Museum

For a little comic relief, we have the cartoonish Hyottoko; a festival favorite with a unique backstory. His most famous trait is blowing fire with a bamboo pole, which is why in Japanese his name translates to fire (火 hi) man (男 otoko).

There are many legends of Hyottoko, but in one version from Iwate tells the story of a boy with a strange face who would produce gold via his belly button. To bring good fortune to families when a member died, they’d place a mask of the boy’s likeness above the fireplace. This boy was named Hyoutokusu, which some say was the origin of Hyottoko. In other parts of Japan, he is thought to be the god of fire. Easy to find in traditional Japanese gift stores and during festival season, more traditional Hyottoko masks are wood, but you can find throwaway plastic versions all over the place.

This Hyottoko mask from the 19th century is actually not a mask at all, but a carved likeness in the form of a netsuke. Netsuke are the sculpted wooden toggles that would be used to hang a pouch from a kimono belt.

4. Okame

© Ivory Okame Mask, 19th Century, LACMA

The cherub-faced Okame is the wife of Hyottoko, a cheerful lady who’s a symbol of good luck. Technically Okame goes under two names; Otafuku and Okame. Otafuku means good fortune while Okame means tortoise a Japanese symbol of a long life, so no matter which name you’re using she’s a positive sign all around.

Like Hyottoko, Okame masks are rather ubiquitous, especially in smaller regional towns. Chances are you won’t have to look hard to find an Okame mask either in wood, paper mache or plastic. These days you’re less likely to find a mask in ivory such as this one, although I think we can agree that’s for the best!

f you’re looking for beautifully crafted souvenirs, Japanese dolls have a fascinating history. Find out more at 8 of The Most Exquisite Traditional Japanese Dolls!

5. Namahage

© Chris Lewis / Creative Commons, Namahage Festival

In the western world, parents lean on the omniscience of Santa Claus to keep children in check; but for residents of Oga city in Akita, the Namahage is a concept far more fearsome than coal in your stocking.

Each New Year the young men of Oga village don these terrifying Japanese masks of mountain demons (Namahage) as a way to scare children into behaving. It's a strange but fascinating local folklore tradition that’s shaped the town’s identity so heavily that it’s near impossible to walk down the street or visit a store in Oga without coming face to face with a namahage. Stylistically the wooden and paper mache masks vary depending on the area in where they were created, but they all share unifying grotesque features, sharp teeth and a rugged ugliness that’s impossible to forget.

6. Men-yoroi

© Samurai Armor, 18th Century, the Met Museum

Also referred to as Mempo, Men-yoroi is the umbrella term used to describe the protective and decorative facial armor worn by Japanese samurai. Under the men-yoroi title, there are many different kinds of samurai mask including somen, menpo, hanbo or hanpo, and happuri. Some, like this 18th century example, covered the whole face while others only partially. Although they served a fundamental practical purpose, the masks are worth admiring from an artistic perspective.

Many masks feature a combination of iron and leather, while other sport lacquered finishes with extra detailing like detached noses and untamed facial hair. If you look up close, you could imagine how coming face to face with these masks would instill fear in the even the bravest of warriors.

7. Kitsune

© Wooden Kitsune Fox Mask, 19th Century, LACMA

One of the most enigmatic and ubiquitous figures in Japanese folklore, kitsune (狐) in Japanese means fox, but the figure of kitsune is much more than your standard farm-lurking, four-legged pest.

According to Shinto beliefs, the kitsune is a messenger of Inari, the god of fertility and agriculture, but is not always a figure of upstanding ethics. In some ways, kitsune also represents the contradictory nature of every single one of us, which is why it’s become one of the most recognizable Japanese masks in popular contemporary culture. Available in a variety of forms, you’ll find traditional kitsune masks in costume, souvenir, and gift shops everywhere.

Find out more at 6 Things You Should Know About Kitsune!

8. Tengu

© Tengu Masks, 18th Century, the Met Museum

Tengu, with his glowing red face, protruding, bulbous nose and typically rather grumpy expression is one of Japan’s most multi-faceted figures. Tengu is a type of Shinto god with roots in Chinese religion, inspired by the image of the Chinese dog-demon (Tiangou).

Although Tengu looks most like a red-faced wizard, they were believed to be birds of prey, easily fooled by humans, sometimes evil, sometimes good depending on the legend. Take a look at these 18th century lacquered masks and you can decide for yourself which facet they represent!

You’ll typically find traditional tengu masks made from wood, paper mache, and plastic. Today they’re worn in theatre performances, featured in festivals and often hung in houses as symbols of good luck, believed to frighten bad spirits. If you feel like you’ve seen Tengu before and can’t quite put your finger on where check your iPhone keyboard, he’s been immortalized in emoji form since 2015!

9. Bugaku

© Lacquered Wooden Bugaku Mask of the Dragon King, 17th Century, British Museum

Less well known than Japan’s other performing arts, Bugaku is a dance performance that’s been practiced in Japan for centuries. Like Noh, it requires performers to wear thick, carefully crafted masks, but that’s where the similarities end.

Originally Bugaku was a dance performed for the country’s imperial court and social elite. Unlike the rigidity of Noh masks, however, some Bugaku masks feature movable parts, like the chin on this 17th century mask. There are about 20 regular characters in Bugaku, each with their unique personality and of course mask, created with dry lacquer or wood. This particular mask represents the Dragon King, who was said to have been so handsome that we was forced to wear a mask into battle to be able to inspire fear in his enemies.

10. Oni

© Wooden Netsuke, 19th Century, Mudec Museum of Cultures

Visually Oni looks a lot like Tengu, but with far smaller noses, but they are two entirely different beings. They’re incredibly common in Japanese folk legends, and depending on where you hear the story have very different origins. This wooden Oni is another small netsuke carved in his likeness.

The biggest event on the Oni calendar is Setsubun, a celebration of spring (held the day before the beginning of the season) where festival goers throw beans at people wearing these Japanese festival masks as a way to cleanse evil and celebrate the return of the country's favorite season. During this time many parents wear the scary masks to frighten their children all in the name of fun.

Do you have any Japanese masks? Let us know in the comments below!

ART | February 5, 2022