The Secret Hideaway of Japan’s Best Nihonga Artists

by Alice Gordenker | ART

Spring from the Four Views of Mt. Fuji by Taikan Yokoyama, 1940, Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki

One of the most important chapters in the development of modern Japanese painting unfolded in a remote seaside hamlet that is virtually unknown. Yet today the village of Izura, situated on a beautiful rocky coast in northern Ibaraki Prefecture, is easily accessed from Tokyo and offers a perfect weekend escape. Any adventurous art lover can visit the Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki to learn how, in the early 20th century, Japan’s most promising nihonga artists gathered at Izura and together revolutionized Japanese art.

What is Nihonga?

© The Sound of Waves at Izura by Toshio Matsuo (1926-2016), 1991, Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki

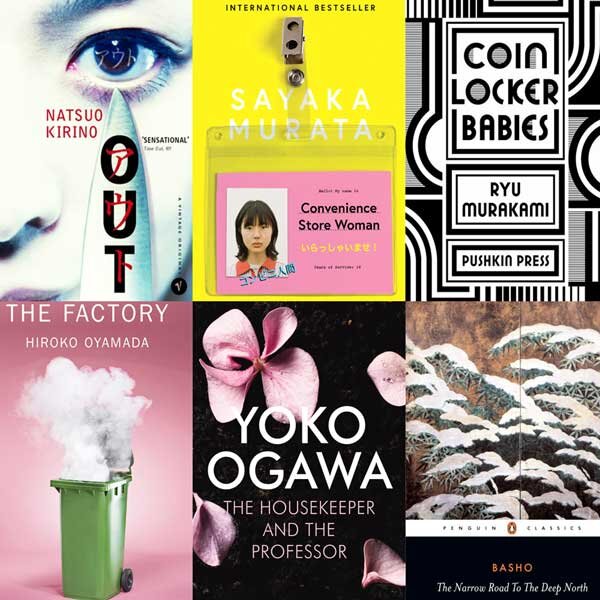

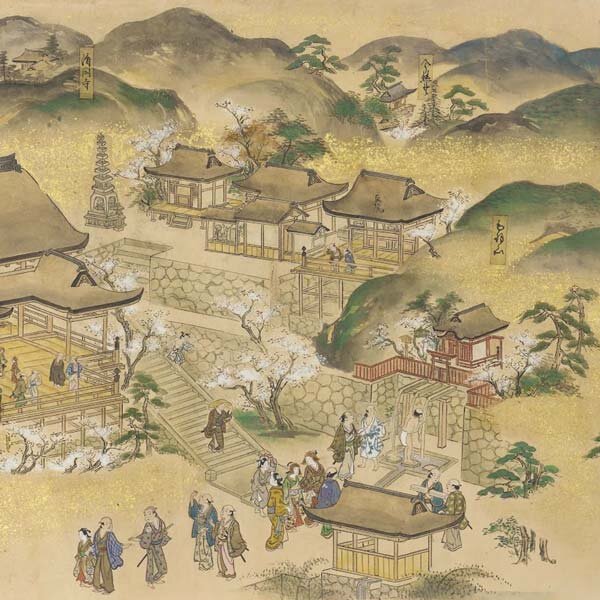

Nihonga literally means Japanese painting but it’s a relatively recent term, coined during the Meiji period after Japan opened to the West, to distinguish Japanese painting from Western-style oil painting. Definitions tend to change, and these days, when many nihonga painters draw inspiration from Western art rather than limit themselves to traditional Japanese themes, the distinction is best explained by the differences in materials used. In nihonga, the support is generally paper or silk, not canvas, and the paints are made of finely ground minerals mixed with an animal glue as the adhesive. Ink is also widely used in nihonga, as is gold and other metals, applied as paint, powder or thinly pounded metal leaf. Find out more about this fascinating Japanese painting style in our Concise Guide to Nihonga. You don’t have to be Japanese to be a nihonga artist; there are artists all around the world who express themselves using nihonga materials and methods.

Who was Tenshin and Why is There a Museum Named After Him?

Fallen Leaves by Shunso Hishida, 1909, Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki

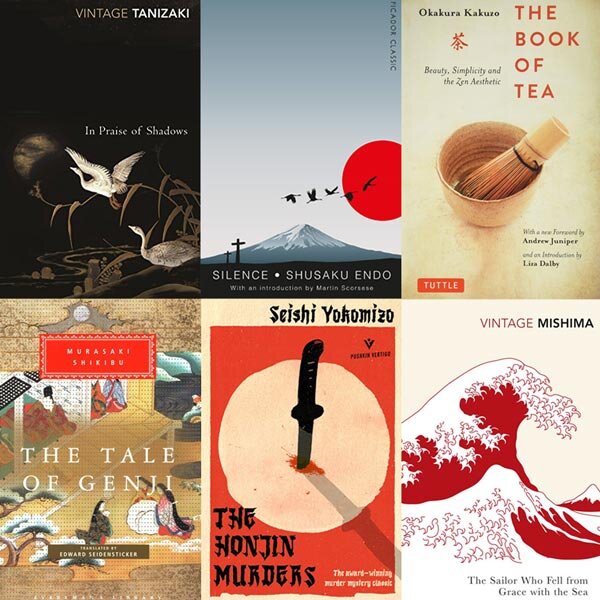

The first stop on a trip to Izura should be the Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki, which offers excellent background and almost always has nihonga paintings on display. The museum is first and foremost a tribute to Kakuzo Okakura (1863-1913), who is best known in the West as the author of The Book of Tea. (The museum draws its name from the pseudonym Okakura used when writing poetry.) As a young man, Okakura met the American educator and art historian Ernest Fenollosa (1853-1908), who helped him develop a deep appreciation for Asian art and culture at a time when many Japanese regarded all things Western as superior. Together the two embarked on a program to save Japanese antiquities from destruction. Later, Okakura served as curator of Asian art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Nihonga at the Japan Arts Institute

Return from Fishing by Shunzo Hishida, 1901, Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki.

In 1887, Okakura helped found the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, now called Tokyo University of the Arts and one of the finest art schools in Japan. He served as its first director but was ousted in an administrative struggle. In reaction, in 1898 he created a new institution called the Japan Arts Institute. Among the first students were Taikan Yokoyama, Shunso Hishida, Kanzan Shimomura and Buzan Kimura, all of whom became key figures in the Nihonga movement, which sought to revitalize indigenous painting in the face of the rising influence of Western art. In 1906, Okakura moved the institute from Tokyo to Izura, where he had built a house, taking his four best students with him. It was an odd move, mocked by the art establishment in Tokyo as both defeat and retreat, but it allowed the group to focus as never before.

A New Japanese Painting Technique

Morning at Izura by Buzan Kimura, 1906-07, Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki

At the time, Japanese painting was widely regarded as flat and primitive compared to Western painting. The primary complaint was that it lacked the mechanisms used in Western art, including scientific perspective and chiaroscuro shading, that create dimension and variations in light. Convinced that Japanese painting could not compete unless this perceived deficiency was overcome, Okakura challenged his students to find new ways of expressing air and light. Rather than borrow from the West, Okakura urged them to look within the traditions of China and Japan so that their solution might be authentically Asian.

Dew Drops at Ohara from The Tale of Heike by Kanzan Shimomura, 1900 Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki

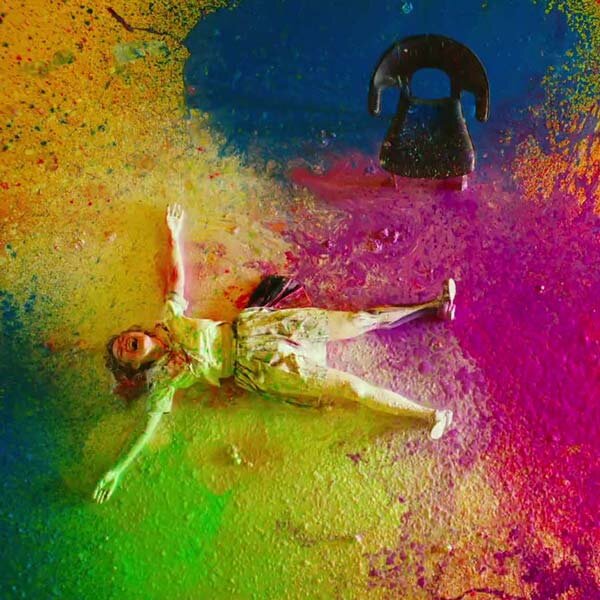

One approach the talented young artists tried was to do away with the strong outlines that previously characterized Japanese art. Instead, they used wash techniques to put down pigment in subtle ways so that colors or tones seemed to melt into one another without perceptible transitions, lines or edges. This, too, was initially ridiculed by critics, who gave it the pejorative name morotai (blurred style). Undaunted, the group at Izura persevered with the unconventional style, making modifications and eventually winning acceptance. Hishida and Yokoyama came to be recognized as masters in this highly atmospheric way of painting; their works are included in the collections of top museums around the world.

Modern Nihonga

Morning Mountain Range by Koichi Nabatame © 2018 Japan Art Institute.

The collaboration lasted less than two years, from late 1906 until June 1908, when Hishida had to return to Tokyo to receive treatment for illness. Okakura too departed for the United States to direct a new department of Asian art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the rest of the group disbanded. A year after Okakura’s death, Yokoyama revived the organization in Tokyo, where it continues to this day as the single most important institution for the promotion of nihonga.

Nihonga as a uniquely Japanese style of painting remains a vibrant part of the contemporary art landscape. Read our exclusive interview with prominent nihonga artist Rieko Morita whose signature floral paintings can be found on the 800-year-old cedar doors in the main hall of Kyoto’s famous Kinkakuji (Golden Pavilion).

The Annual Inten Exhibitions

Itsukushima Shrine by Toshio Tabuchi © 2018 Japan Art Institute.

Today, the most important function of the revived Japan Art Institute is the organization and promotion of twice-yearly exhibitions known as the Inten. The annual Spring Inten Exhibition, now in its 74th year, always opens at the Mitsukoshi Department Store in Tokyo. (This year, it ran March 26 to April 8 in the store’s galleries before starting on a tour to 16 locations around Japan.) The Autumn Inten Exhibition, which has been held 103 times, makes its debut at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and then travels, including a stop every other year in Izura at the Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki. The contemporary images in this article are part of the 103rd Inten Exhibition, on view at the Imai Museum in Gotsu, Shimane Prefecture through April 21 before its final showing at the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art, April 26-May 26, 2019.

Don’t worry if you miss it, there are plenty of other opportunities to enjoy contemporary nihonga art; check out these 12 modern nihonga masterpieces for a good start!

Visiting Izura

Poppies by Koji Matsumura © 2018 Japan Art Institute.

The permanent exhibition at the Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki is accessible to international visitors. You could arrive with no prior knowledge and come away with a sense of who Okakura was and why his time in Izura was important, but the exhibits are captioned only in Japanese so be sure to pick up one of the free headsets at the information desk so you can listen to the audio guides with channels in English, Chinese and Korean. The museum also organizes six or seven special exhibitions a year, usually on a theme from modern or contemporary Japanese painting. Be forewarned that the audio guide doesn’t cover temporary shows.

Summit by Wang Pei © 2018 Japan Art Institute.

Visitors to Izura can also see Okakura’s home and the Rokkaku-do (Hexagonal Hall), a seaside pavilion he built for contemplation and tea ceremonies. The distinctive red structure was swept away in the tsunami of 2011 but rebuilt a year later with donations from all over the country. The Izura Kanko Hotel has renovated the studios used by Taikan Yokoyama and Buzan Kimura during their time in Izura into beautiful Japanese-style suites that can be rented by the night. Sleeping in the actual space where such creative geniuses worked makes for a particularly memorable stay.

How to Get to the Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art

Tenshin Memorial Museum of Art, Ibaraki

Address: 2083 Tsubaki, Otsu-cho, Kita-Ibaraki City (see map)

Website: tenshin.museum.ibk.ed.jp

Hours: April-September, 9am to 5pm (no entry after 4:30) and October-March, 9:30 am to 5pm (no entry after 4:30). Closed on Mondays except when Monday falls on a national holiday, in which case the museum is closed the following day. The museum is a branch of the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki.

Access: From Tokyo, take the “Super Hitachi” or “Fresh Hitachi” limited-express train on the JR Joban Line, boarding at Shinagawa, Tokyo or Ueno and riding about two hours to disembark at Isohara station. A taxi to the museum from this station takes about 15 minutes. Alternatively, change to the local train and ride one more stop in the same direction to Otsuko station, for a shorter taxi ride of about 5 minutes. A few limited-express trains stop at Otsuko.

Which image makes you want to pack your bag for Izura? Let us know in the comments below

Images courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, Ibaraki and the Japan Art Institute.

ART | October 6, 2023