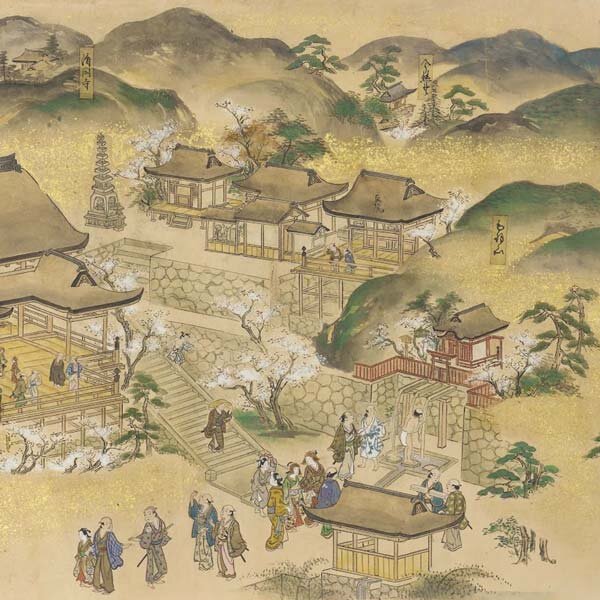

© Tetsuya Miura, Ikebana by Nishiyama Hayato

As our lives become ever more satiated with things and clutter, the philosphy of less is more becomes ever more appealing. In Japan, minimalism has been a part of art and philosophy for centuries, so it makes sense to look to the country for inspiration on how to live an uncluttered life. Whether looking back to Japanese minimalist art, or minimalism as a design philosophy in the home, or the works of modern lifestyle writers, you can certainly find a way to incorporate principles of Japanese minimalism into your everyday life!

1. Pine Trees by Tohaku Hasegawa

Pine Trees by Hasegawa Tohaku

The folding screens, Pine Trees, painted between 1539–1610 by Tohaku Hasegawa is considered a national treasure of Japan. In contrast to the grandeur styles and trends of the late 16th century, works like Pine Trees and other modes of rustic simplistic art practices such as the tea ceremony made its own resistance against the decadence of the time. This appreciation of the rustic, of impermanence, of non gold painted pieces can be seen in Pine Trees. Although some of Hasegawa’s other work features more elaborate tastes, Pine Trees is made up of simple, quick brushstrokes to create space, layers, and light. According to an interpretation by the Tokyo National Museum, the painting more or less captures a quintessential Japanese ink painting due to its innate simplicity, the lack of gold, and the use of ink as the sole aesthetic to create depth.

Enjoy more of Hagesawa’s works at Hasegawa Tohaku: The Timeless Giant of Japanese Art.

2. Raku Yaki, Chojiro & Wabi Sabi

Tea bowl with black glaze attributed to Chojiro, early 17th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In a similarly unique, rustic vein of the late 16th century, raku yaki (raku ware) makes a statement in it’s unassuming form. Originally hand made by Chojiro, the Raku family founder, raku yaki mainly consists of red and black tea bowls. These tea bowls were requested by wabi sabi tea master, Sen no Rikyu, who embodied a humble lifestyle that embraced imperfection and incompleteness. Chojiro’s work, and the many raku yaki works that followed in the years to come demonstrate an avante garde austere quality that we still associate with wabi sabi and minimalism today. Applying something new (although subtly) to something old, a slight change, or a small mistake that endlessly inspires.

Learn more at Raku Pottery: Everything You Need to Know!

3. The Moriyama House by Ryue Nishizawa

© Ryue Nishisawa, Moriyama House

Many are quick to point to Japanese architecture when it comes to the distilling nature of its minimalism, often also associated with the modern and inherently compelling. In sprawling cities like Tokyo, the Japanese house adapts and gracefully (at times) attempts to hold a certain space of flexibility and function. The Moriyama House does this by creating the possibility of communal space, highlighting the relationship between private and public. This grouping of small buildings, ten in total, emphasizes the solidarity of a singular room, and yet its thin walls seem to imply the crumbling of a private space that unfolds into something shared. The steel plating of the walls was intentionally designed to create more interior space. The use of certain materials to create a more livable environment in the chaos of Tokyo is arguably one of minimalistic taste, a desire to live neatly despite the ever-changing, growing, and fleeting neighborhood outside.

Find out more about Japanese architecture Inside 5 Timeless Traditional Japanese Houses.

4. Ikebana by Toshiro Kawase

© Tetsuya Miura, Ikebana by Nishiyama Hayato

“The whole universe is contained within a single flower” says ikebana artist Toshiro Kawase. In this centuries old art form, the principles that shine through are minimalistic in nature. Historically, ikebana, or Japanese flower arranging, began as a kind of offering to the gods, a way to integrate the human world with the holy counterparts. Throughout the years, it evolved into a formal practice in arrangement, the guidelines of which have seen subtle changes throughout the years, especially in regards to how much the rules are adhered to or slightly ignored. The relationship between these two extremes, among other philosophical ideas, is represented in the juxtaposition of flowers presented, whether a bud, or a stem.

In his photo book, Inspired Flower Arrangements, Kawase plays with dualities and new ways to express the craft, or better yet a fleeting sense of life in all its variety, with incredibly minimal but fundamental tools: flowers, moss, soil.

Try your own hand at ikebana: All You Need to Know About Japanese Flower Art.

5. Deja Vu Stool by Naoto Fukasawa

© Naoto Fukasawa, Deja Vu Stool

The renowned Naoto Fukasawa is an industrial designer, and a respected artist of the chic minimal creation of every day and otherwise regular items. Fukasawa designs anything from bags, interior spaces, and various types of furniture. Founding his own studio in 2003, and on the board for companies like Muji, Fukasawa is a highly sought after creator for the unique way he controls a space. The Deja Vu Stool, one of many stools and chairs of a similar name stands out, and yet it blends. Not so dissimilar from the train of thought that a stool is a stool is a stool, his design is pleasing, and industrious. Fukasawa was quoted in 2015 in a statement about his work, unconscious human behavior, a concept he continues to play with in each project he undertakes, including the simplistic elegance of the Deja Vu Stool family.

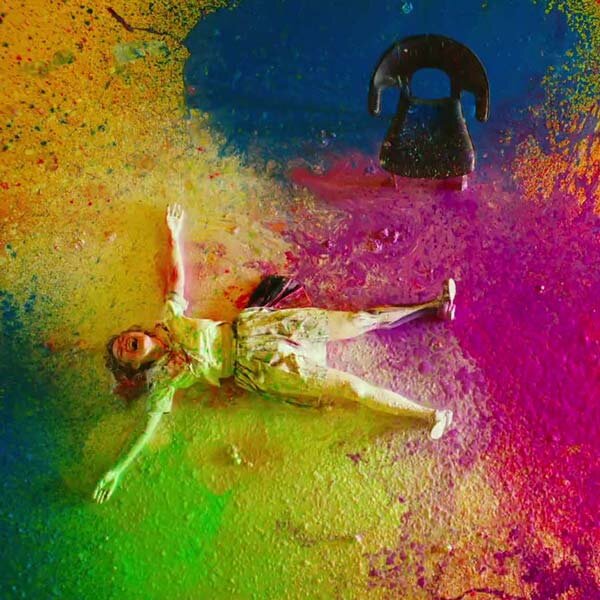

6. Sankai Juku

The butoh dance group, Sankai Juku, founded in 1975 by Ushio Amagatsu, utilizes the stage and minimalistic materials to tell a story in addition to the choreography of bodies. In their performance, Umusuna (an old word for place of birth), a layer of sand covers the stage and falls from above continuously in the center stage. By the end of the dance, the sand has moved around and the audience can clearly see the impact of the dancers movement. An interview with Amagatsu in WochiKochi magazine he says, “I like the idea of stage art that changes with time. That's why I use things like sand or water that bring tangible qualities into my work.” Unlike other works on stage, and much unlike our own modern concept of time, Sankai Juku works to blur our idea of time existing in separate places, combining seasons and breaking linear structures. The Routledge Companion to Butoh Performance says “Thus, a certain moment does not become obsolete with time.” In this way, everything is present.

7. Paris-New York Drawing no. 144 by On Kawara

© On Kawara, Paris-New York Drawing No. 14, 1964

Famously known for being defined solely by his work (his absence felt at his own exhibitions) On Kawara documented his own life meticulously and without fanfare. This can be seen in the sheer amount of works he created, up to about 3,000 individual pieces. His dedication and consistency was not so unlike a meditative practice, the projects he created highlighting the daily and the almost mundane, but with some slight variation. Paris-New York Drawing no. 144 is one of 200 drawings he made whilst back and forth between Paris and New York in the 1960’s. The drawing seems to reference Minimalist painter Agnes Martin in its lightness, and grid-like presentation. Despite the appearance of simplicity in these works, Paris-New York Drawings give off an unsettling feeling. Kawara’s graphite and colored pencil on paper is a stark example of minimalism doing figurative, long-term work. His later work continues to play with these ideas, albeit with more lyrical attention with titles like Title, Today Series, and I am still alive. Later he would become one of the artists used to define what is now called “conceptual art.”

8. Final Home by Kosuke Tsumura

© Kosuke Tsumura, Final Home

Fashion designer, and dystopian brand connoisseur Kosuke Tsumura pinpoints his creations around the idea of sustainability and utility function. In Final Home, we find a jacket with pockets, zippers, and ideal placement of survival tools, meant for actual apocalyptic use and yet also meant to provoke. Interestingly, Tsumura’s work is more often identified as projects instead of as a brand. This can be exemplified in Final Home where a jacket is a place to live, a concept of a mobile resting place if and when all else crumbles into oblivion. Where brands capitalize on production and sales of many, the Final Home jacket prioritizes the one. It’s the only item you’ll ever need. However, the high retail price of the item makes it inaccessible to those who actually need it. To counter this, Tsumura includes a card with every purchase asking the owner not to discard it, but to bring it back to the original maker to recycle and reuse. After the garment is returned, Tsumura gives it to those who need it most.

9. Marie Kondo’s The Life-changing Magic of Tidying Up

Internationally known as the Netflix series Tidying Up With Marie Kondo that became a sensation, this book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, was the beginning of a very visible minimalism trend in 2011. Marie Kondo is a self-proclaimed cleaning consultant, advising her fans and clients alike to declutter with care, and ultimately give your life a healthy, wholesome makeover. The term spark joy is still buzzing around meme corners and dropping casually into everyday conversations. The impact of this brand of minimalism reminds us that an idea is consumable, to the extent of adopting it into our lives. In this way, Tidying Up with Marie Kondo is a form of capitalistic, albeit accessible, minimalism that becomes our own. The book itself teaches more than tidying, Konmari reiterates the importance of intention and putting your mind in order, implying the rest will follow. First and foremost is the philosophy of discarding, which in line with minimalistic tendencies and joy is everything.

10. Goodbye Things by Fumio Sasaki

In contrast to the professional seamlessness of Marie Kondo, Fumio Sasaki gives off the vibe that he doesn’t have his life together, at least he didn’t used to. His method of mottainai and less is more is more of a reaction to a life that wasn’t bringing him constant joy (What is Mottainai? Japan’s Eco-Friendly Philosophy). In his book, Goodbye, Things, the reader is transported into a very personal and relatable story of change. Similar to Marie Kondo, he offers advice on how to alter your life, and highlights the importance of transforming your surroundings in order to completely capitalize on a life that brings you more peace. Sasaki’s book was published in 2015, in a time where the minimalist way of life was already in itself a movement, a lifestyle, a brand; it’s trending. But his attempt is clear: to make it more accessible to everyone, and to take off its capitalistic shine. An article in Japan Times quotes Sasaki: “Whether we live alone or with other people, few acknowledge the presence of another roommate,” Sasaki writes. “This roommate is named ‘Things’ and the space that ‘Things’ occupies is typically a lot larger than the space people have for themselves.”

JO SELECTS offers helpful suggestions, and genuine recommendations for high-quality, authentic Japanese art & design. We know how difficult it is to search for Japanese artists, artisans and designers on the vast internet, so we came up with this lifestyle guide to highlight the most inspiring Japanese artworks, designs and products for your everyday needs.

All product suggestions are independently selected and individually reviewed. We try our best to update information, but all prices and availability are subject to change. As an Amazon Associate, Japan Objects earns from qualifying purchases.

ART | October 6, 2023